Singer-songwriter, musician and author, Dan Stuart's career spans four decades. Over that period, he has recorded over two dozen studio albums; his back catalogue consists of his solo work as band leader with Green on Red and The Slummers and collaborations with Al Perry and Steve Wynn. His literary work includes the Marlow Billings trilogy of novels and his book of poetry, Barcelona Blues. In the early to mid-80s, Green on Red was at the forefront of The Paisley Underground movement in California, providing some of that decade's most essential music. He spoke recently with Lonesome Highway of that period in Los Angeles ('I'm lucky those guys even talk to me') and much more.

We are looking forward to your return to Ireland. What can we expect from your shows?

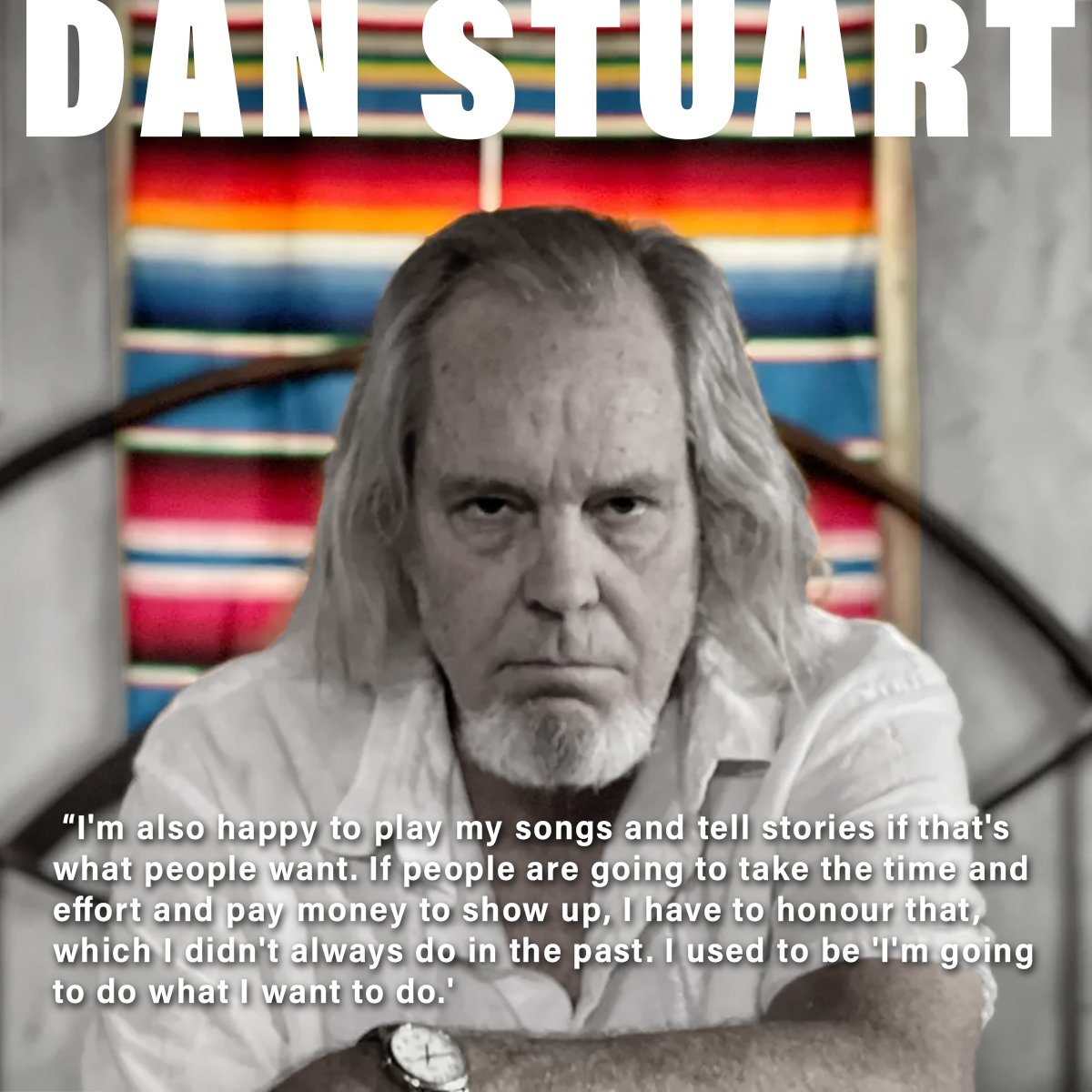

I'm not sure yet what is expected of me at all the shows, I think some are more literary-oriented than others. I'm also happy to play my songs and tell stories if that's what people want. If people are going to take the time and effort and pay money to show up, I have to honour that, which I didn't always do in the past. I used to be 'I'm going to do what I want to do.' With the way society and our greater culture are these days, and coming out of all the things we've been going through in this last decade, we really need to reestablish that beautiful contract between performance and audience and give mutual respect in both directions

You have two appearances lined up for the Kilkenny Roots Festival.

Yes, the Kilkenny Roots Festival, like the Dylan Thomas weekend in Wales that I recently performed at, is something that I have wanted to do for quite a while, and I'm very pleased that I have been invited. I met Willie (Meighan) some years ago in Kilkenny and didn't understand how much he meant to that community at the time. When I did find out about his history, I was very impressed.

You will be sharing stages with two artists with a similar background to yourself, Peter Case and Sid Griffin.

I don't really know Peter, which I'm a little scared of, to be honest (laughs). He's a hell of a musician with a great body of work. I've known Sid forever, and he's a sweet and caring guy who has enjoyed an interesting life in the U.K. He can go on to the BBC and do battle for all of us gringos back home. He's so light on his feet when exchanging witticisms, and he can do all the wordplay and the puns. Not all of us Yankees are that talented.

I understand that your first exposure to punk was not MC5, The Stooges, or The Velvet Underground but Chris Bailey's short-lived Australian band, The Saints.

Well, I was aware of the Velvet Underground, MC 5 and The Stooges when I was thirteen. We had a very good radio station in Tucson, and we got a lot of touring acts that played Tucson because of that radio station and that maybe wouldn't go to Phoenix and places like that. I would have heard all that type of stuff that people now consider the beginnings of punk rock. But I would say you've got to go back to the 50s to really get into that sort of basic sort of one-four-five chord change behind that massive backbeat. The punk rock thing is really interesting because I was bored of rock and roll around 1974. I went to Australia with my dad, who was Australian. He was a professor, and he went over there for a sabbatical. So, I spent a year in Australia on Maroubra Beach, of all places. So, I was living in Australia when The Saints' I'm Stranded was the number one hit. This was like 1975/76. But I also saw Radio Birdman at the Royal Easter Show, which was a big County Fair type thing in Sydney, and I was tripping on acid, so that was quite a shock. But when I got back to Tucson, punk had really just taken over, and I had already seen some of it. So, when I came back from Australia, everybody was talking about The Clash and The Ramones. I caught all that when I was about sixteen.

What are your earlier music memories?

You don't get to choose your era, and whatever you listen to, when you first fall in love, or when you first have your bit of independence from your parents, that will be what sticks with you. But I feel very lucky because in 1968 I was seven years old, driving around with my mom and in the car listening to great pop radio and the beginning of what we now call album-oriented rock or classic rock, which was dominant on F.M. radio back then. Then, in the early 70s, when I first started smoking weed, we listened to what we now call prog, but for me, rock and roll was getting a little bit too intellectual, with too many chord changes. I had the best with Burt Bacharach, The Monkees, The Doors, Bob Dylan, prog, album-orientated rock, and then punk.

All those influences put you on your own musical path.

Yes. All that stuff leaked out when I started doing music with my friends. I wish I had been a better musician to take advantage of what I had heard. That's been a real struggle over the years to get the craft where you can really manifest what you're feeling. That was a long struggle for me; I wasn't, and I am still not, a very good musician. It doesn't have to be perfect, but you've got to be able to deliver. I have a saying that I always try to be the least talented in any collaborative endeavour. I've been really lucky with everybody I've worked with, from Chris Cacavas and Chuck Prophet, and right on until my very last record that I did with Danny Amis producing. I'm like Blanche DuBois, you know, I depend on the kindness of strangers. I've been very lucky that way, and with my writing, too, I've had a few really important readers of all my books that have helped me get better each time, which is a nice feeling. As a writer, it's nice to feel you're getting better at your work.

Your early band days would have been part of an underground scene in Los Angeles.

Yes, and it's so much harder to be underground this century, the counterculture has gradually disappeared. Everything gets co-opted and sold back to a potential audience within minutes. I like to joke that all my references were last century, I used to think about what it would have been like to be alive around 1920. If you spent most of your life in the previous century, it must have been very strange to have all these references of a time and age that had disappeared. People ask me, well, what do you think about this? What do you think about that? I'm still trying to figure out, you know, 1985. I'm the wrong person to talk to when people want to know about that new Netflix series. I haven't even I haven't even worked my way through the French New Wave yet.

That underground scene most probably does exist. Unfortunately, there are not as many avenues for acts to advance from that as there were in previous decades.

I'm with you on this idea that, regardless, there will be kids getting together in living rooms and basements who are figuring out how to interact with each other and how to play this thing that we used to call rock and roll. I don't think that's gone away, it's just maybe a little tougher to uncover than it used to be. It's a little more invisible. My son was in a punk band for a while as a teenager. He lives in New York City and they very much had their own little circuit. They had little places where they were playing, but the difference is that there was no New York Rocker magazine to talk about it.

That absence, or lack of quality music press, in America is lamentable.

What particularly hurts, and not just in music, is that we're out of the age of criticism and more kind of in the age of celebrity. There's also this egalitarian thing about deciding what's good and what's not. Well, I don't care whether we're talking about a Vietnamese restaurant or some new flick out of Turkey or whatever. I miss honest criticism and negative reviews, which I think are very important. It never bothered me when somebody took the time to give a nice burn to myself or Green on Red, and I appreciated that somebody cared enough to give us a wallop. But I'm a snob, not when it comes to politics or economics or things like that, but when it comes to the arts. I want to hear somebody's opinion, especially if it goes against my initial point of view. As we both know, a well-written piece of criticism is not about declaring something good or bad. It's deeper than that. Because life itself is so nuanced and complicated. I am fortunate to have experienced much of that firsthand and caught the last days of real publishing money and rock and roll criticism. I miss that; I miss the Lester Bangs and Nick Tosches of the world as much as I miss the classic rock bands.

With Green on Red, did you feel part of a growing movement that became tagged as The Paisley Underground?

Well, we did get lumped into the quote/unquote, The Paisley Underground scene. We weren't friends with all the others; some of the bands we didn't even know, but we knew The Dream Syndicate and Rain Parade for sure. We would have parties and barbeques, go out drinking, and go to each other's gigs. We were all in our early twenties in L.A. having a blast.

Did you view it as a path to commercial success?

I was too insecure to take advantage of what might have been lined up for us. Lee Hazlewood told me that These Boots Are Made for Walkin' put all his kids through college. But I wasn't thinking along those lines in my twenties and even if it would have been attainable, I would have been, and I'm taking responsibility here, the one to sabotage that simply because if it didn't happen, I wouldn't be disappointed. That's a common thing with a lot of young people, 'if I really admit that it would be nice to hear myself while I was grocery shopping, I might be disappointed if I didn't.'

Was there industry support there for you to widen your appeal?

Green on Red got away with murder; we were given a chance after chance after chance and blew it. Then I went and fired the band, my best friends. I didn't even tell them all, they had to find that out through the music press. Anyone trying to help us was like trying to help a sociopath, it was not going to work. At the same time, I'm proud of Green on Red, and I'm most proud of the fact that the four of us, the surviving members, are still on a certain level like brothers. I'm not ashamed to say that I love them and that outside of my immediate family, they are some of the most important people in the world to me. It's like the Paul Thomas Anderson movies where your original family is not good enough, and so you start another one in your adult life. We're in regular contact, and they are far better people than I am; I did some really dreadful things. I'm not saying that to beat up on myself, and I'm not a big guy on redemption, but I did some crappy stuff, and I'm lucky those guys even talk to me. But that relationship of us all climbing into the van and going around the world was heavy stuff. It's deep, as Jack (Waterson) said to me recently, it's as close to going to war as you're going to get.

You have all survived and are enjoying successful careers?

Yes, what about Jack and his hip-hop career with Adrian Younge? He has had the most interesting career of all of us because he is in a totally different world. Chuck and Chris have done extremely well, too; we took our experience and leveraged it into something that was more important to us as adults.

How did you deal with the transition from band leader to solo performer?

I had to learn to do the 'folkie' thing around 2010. It's not easy though I've got a lot better at it. I did a book tour in September and October last year where I read a few chapters, sang some songs, and told some stories. Because it was neither fish nor fowl, it was easy to do and entertaining. This more recent fifteen-day tour with Tom Heymen was back to doing as Doug Sahm used to say, 'can't sing, can't writer' instead of singer-songwriter. Of course, it's much easier to go out with a decent rhythm section and play rock and roll than do the precious sort of folkie thing. Having said that, it can be lots of fun, and I'm happy that I've forced myself to do it, though it did take a long time to know how to do it.

You recently expressed that you would prefer to have more novels and fewer albums in your back catalogue. Would you have held the same ambition in your early career?

Well, I also wanted to write back then, but I just couldn't do it. I've always considered myself to be a lazy writer, and that's probably why. Writing a song is like a fifty-metre sprint, it may take a year to finish, but you know you have something within minutes. A novel is like a marathon and takes a whole different frame of reference. I would say that half of my records are ok, and I feel the same sort of thing with my books. They all probably have something worthwhile about them, but I still need to do THE one (laughs). Coming off my recent U.K. tour with Tom Heyman, we were actually talking about 'add a word, get a third' co-writing. Writing a novel is lonely, and you're thinking, 'Is this worth anything?' One thing that is a huge relief to me now, because I'm not writing songs, which can be a curse, is that I can practice guitar without writing a song. I'm not saying I'll never write a song again, but I'm done with writing a collection of songs that become albums, that horse has left the barn. I don't think that collections of twenty minutes of music on each side of a vinyl record is something that is adhered to any more, even if the way I grew up listening to music. There is an expression in Spanish', No Tengo Ganus', and like that, I don't have the desire or passion for doing that anymore. That has been hugely liberating for me.

What project in your extensive back catalogue are you most proud of?

I'm proud of the last book, Marlowe's Revenge because I got out of the way of the story and let myself do something that the average person could read. That made me happy, but I'm not a big fan of myself. When you look at what's out there and the number of brilliant musicians, writers, artists, photographers and critics, I've got my own little corner that I sit in, and I don't want to take up all the oxygen in the room anymore. I feel very lucky just now, after my world fell apart in 2009, that I have to pinch myself. I've had a good run, getting invited to do shows and getting the trilogy of novels and records done. I do want to say to you and the audiences that get enjoyment from what I do, “That's a wonderful thing, and thanks for giving a shit.”

Interview by Declan Culliton